May 22, 1919

It had been a normal workday for the day shift at the Douglas & Company Starch Works plant in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. A starting box malfunction at 5:45 p.m. had briefly delayed their departure, but the problem was soon fixed and workers on the night shift came in, allowing them to head home.

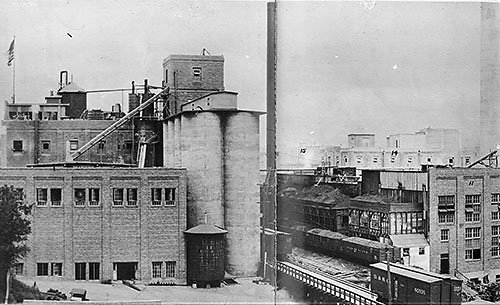

Douglas & Company was founded in 1894 by brothers George and Walter Douglas. It produced cooking starch and oil, laundry starch, soap, and animal feed. Walter died on the Titanic in 1912 but George continued to develop the business and by 1914, the Douglas Starch Works was the biggest starch company in the world.

In May 1919, the plant employed over 650 people and produced 20,000 bushels of corn per day. It was such a major regional employer that no one wanted to imagine what would happen if disaster ever struck.

Explosion

The clock in the timekeeper’s office read close to 6:30 p.m. when a massive explosion rocked the building, which was located on First Street SW, just off of C Street SW. The walls collapsed, pieces of the factory were hurled up to two miles away, and smoke billowed in the evening sky.

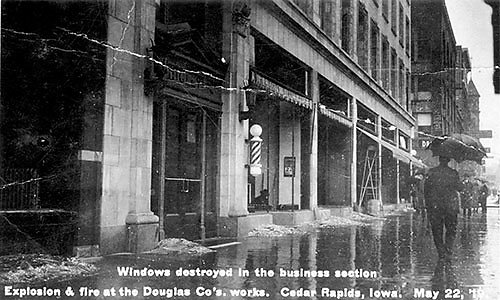

All across the city, homes and commercial buildings shook in their foundations. Glass windows shattered, sending shards flying over the shocked residents below. Over 200 homes were damaged. Across the Cedar River, a young child was thrown from a couch and died as the impact rocked their home. One man standing on a bridge spanning the river was thrown to the ground while those working in the plant suffered serious injury and some men were killed.

Twenty-four-year-old James Newbold was talking to a coworker when the explosion hit. The co-worker was blown to safety but chunks of broken concrete hit Newbold and buried him alive. Rescuers later uncovered his body in the ruins of the packing building and identified him by his signet ring.

Another employee, David Hartman, was at work in the basement of the dry starch building when he was buried under a mountain of debris. The wrench he had been holding at the time was later found by searchers (which included his brother) moments before they discovered his body.

C.C. Pugh, a Des Moines resident who was in Cedar Rapids at the time, shared his recollections months later in a letter to the Gazette, which was the city’s leading newspaper.

“The main explosion seemed to lift great buildings and hold them in tension for a moment, letting them drop with their own weight. Quickly, a haze gathered, holding within its folds an acrid odor, in places almost stifling.

“The details have been given through the papers all over the state, but to know the real effect one had to have been there. Rolling clouds of smoke, permeated with gas, hung in fantastic form for hours (before) drifting away slowly to the east, reddened from the reflection of the leaping flames and turning orange as they floated on, gathering mist and vapor.”

At first, residents thought that the city was under German attack. World War I had ended only six months previously, and people were still struggling to believe that the nightmare was really over. Now they were wondering if they’d been right to be skeptical.

It would later be claimed that a small fire, not a German bomb, ignited cornstarch inside the factory. However, no one knew this at the time. As the smoke cleared and rescue efforts were underway, all that anyone knew was that 43 workers were killed, along with a small child, and 30 others injured. People wanted answers.

Rescue Efforts and Aftermath

George Douglas and his wife, Irene, were enjoying dinner when the explosion occurred. He hurried to the site while she immediately started preparing their home at Brucemore mansion for use as a hospital if the number of injured people was greater than local hospitals could handle.

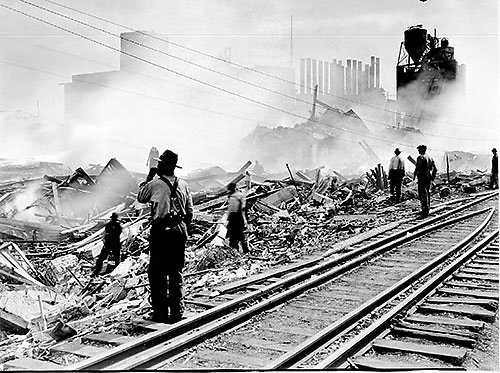

When word of the disaster spread, people poured into town to help with rescue efforts. The fire that raged after the explosion obstructed their progress, and even once the flames were extinguished, residual heat and the sheer devastation kept rescue efforts going on for weeks.

In his aforementioned letter, C.C. Pugh stated:

“The heart of that splendid city was grieved for the dead and dying and their families and they put away everything else, all thought of property loss, all thought of the wrecked condition of their city, to save those in the fiery wreckage.”

Men who were tasked with sifting through the rubble ran through one set of shoes after another due to the still-hot metal debris. The electric searchlights set up to guide them at night cast an eerie glow over the entire explosion site while a steam shovel normally used to handle coal at the plant was given a more sobering task.

Nearly all of the bodies recovered from the debris had a single raised hand, as if the men had instinctively tried to ward off something before they were burned to death or crushed beneath the falling stones, bricks and timber. As each victim was identified, sorrow and shock descended on yet another household.

There were several funeral services throughout the spring and summer. Even the unidentified dead were remembered during a memorial service held at Linwood Cemetery on June 22, 1919. For many families, it was an opportunity to say goodbye to loved ones who would never be seen again.

The Cedar Rapids Chamber of Commerce put together two committees to support rebuilding efforts as well as help those who had lost loved ones in the disaster. In 1919, only 20% of Cedar Rapids women worked outside the home, making them financially dependent on their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons, and the Chamber was anxious to provide them with necessary support. The American Red Cross also set up a disaster relief committee to render emergency aid and help affected families.

Aftermath

A lot of questions arose as a result of the explosion. At the time, there was very little regulation for factories that handled or produced combustible dust, so people began insisting that fire and workplace safety laws and practices receive more attention from the Iowa government.

Their concerns were inspired by comments about questionable safety practices at the Douglas Starch Works plant. One day shift worker had told reporters that some of the men in the plant persisted in smoking around the buildings despite supervisor warnings.

On May 27, an inquiry presided over by Coroner D.W. King ended with the jury finding that the victims had been killed by a “fire of unknown origin followed by an explosion.” No one was ever held criminally responsible for the disaster.

At the end of August, Joseph Hubbell, manager of the National Inspection Company of Chicago, commented on the disaster in an issue of the National Underwriter. It was his opinion that the explosion occurred in the plant’s wet process buildings, where some dry starch may have built up.

He wrote:

“It is now ascertained that projecting air blasts through the doors and conveyors connecting these sections filled them with a starch dust cloud, caused by smashing and upsetting of conveyors, packages, bins, and the like, and went to the end with increasing speed and compression until the building structure gave way.

“It seems clear that as these explosions are initiated almost entirely by manufacturing operations having to do with the dry starch, the grinding mill was probably the cause here. It is clear that the proximity of the mill to other departments and its connection to these by spouts, conveyors and doorways, afforded an easy avenue of spread for drafts and ignition.”

The Douglas Starch Works plant was rebuilt thanks to the efforts of one disaster relief committee, and sold to Penick and Ford in February 1920. The following April, as the site was being prepared for new buildings, construction company employees uncovered a watch and a section of a human hip bone. It was a sobering reminder that they were essentially converting the final resting place of several men who should never have died.

Conclusion

Cedar Rapids has never forgotten those killed in the explosion. In May 2019, 100 years to the day after the disaster, staff and volunteers at the Brucemore museum (the former home of George Douglas) arranged for a wreath to be laid at a monument to the victims in Linwood Cemetery. They also coordinated a public chalking project that marked locations that were affected by the explosion, including the former homes of the victims.

Although over 100 years have passed since the tragedy, dust explosions are as big a risk to health and safety as they were in 1919. Until safety takes priority over cost or convenience, there is always the risk that history could repeat itself.

Many thanks to Brucemore for permission to use the images that appear in this article.