April 27, 1865

Otto Bardon was eager to get home.

A Union soldier who had fought in the 102nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, he had spent part of the Civil War as a Confederate prisoner. Finally the war was over and he was on the riverboat Sultana for the part of his homeward journey.

“On the morning of April 27, 1865, I was in the engine room of the steamer sound asleep, lying by the side of the hatch-hole with seven others of my regiment, when the explosion took place,” he later testified. “First a terrific explosion, then hot steam, smoke, pieces of brick-bats and chunks of coal came thick and fast. I gasped for breath.”

Another Union soldier, Wiley J. Hodges, was sleeping near the boiler when a deafening boom shook him awake. Finding himself covered in burning coals, he threw his blanket away and ran for safety. He ended up throwing a plank into the Mississippi River and jumping in after it.

The loss of the Sultana near Memphis, Tennessee, was the greatest maritime disaster in U.S. history. An estimated 1,800 of her 2,427 passengers were drowned or consumed by the fire. (The exact number is still being debated, but it was high enough for many historians to call the Sultana the ‘Titanic of the Mississippi.’) Others were so badly burned that their lives were never the same.

Despite these huge losses, the tragedy was overshadowed by other events. Only the day before, Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth had been killed and the nation was struggling to rebuild after the tragedies of war. The Sultana casualties, most of whom were soldiers, may have been accepted by a war-weary public as a residual effect of the Civil War.

About the Sultana

Constructed in 1863 by the John Litherbury Boatyard in Cincinnati, Ohio, the Sultana was a wooden steamboat registered at 1,719 tons. She measured 260 feet long, 32 feet wide at the beam and was the classic ‘wedding cake’ design of that period. Although intended for the Lower Mississippi cotton trade, she had frequently been commissioned during the Civil War to carry troops between St. Louis and New Orleans.

The Sultana’s two side-mounted paddle wheels were driven by four fire-tube boilers, each one 18 feet long, 46 inches in diameter, and containing 24 five-inch flues running between the firebox and chimney. Although it could generate twice as much steam per fuel load as regular flue boilers, the fire-tube design had its risks: their water levels had to be carefully maintained and any dip could cause hot spots and metal fatigue, increasing the risk of an explosion. Given that the Sultana’s decks were constructed from varnished, painted wood and coal dust was everywhere on the lower levels, any such incident would end in disaster.

The Tragedy

On April 21, 1865, the Sultana left New Orleans for St. Louis. She stopped at Vicksburg, Mississippi, for boiler repairs that were later deemed substandard: instead of a malfunctioning boiler being replaced, a leaking area was simply patched up and a bulging boiler plate was replaced with a thinner one. This repair job took only one day whereas a complete boiler replacement would have taken three days to complete.

When the Sultana resumed her journey, more than 2,400 passengers were on board. Most of these were Union soldiers recently released from Confederate prison camps. The ship had contracted with the U.S. government to transport these men back home, but with a legal capacity of only 376, she was dangerously overcrowded.

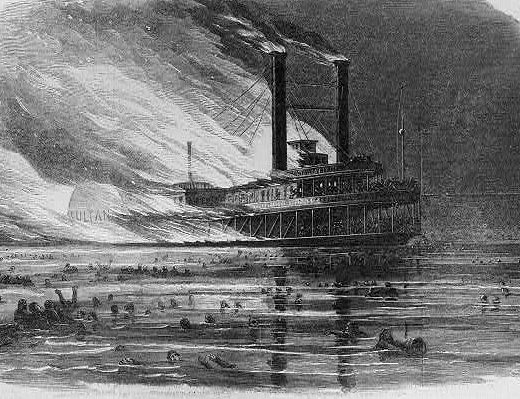

The explosion occurred at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of April 27, when the Sultana was an estimated seven miles north of Memphis. First one boiler exploded, followed by two more a split second later. Steam shot upward, tearing through the decks above and destroying the pilothouse, effectively ending any control of the boat.

The force toppled the twin smokestacks, demolished a large section of the ship and threw passengers into the river. When the upper decks collapsed onto the exposed furnace boxes, they caught fire and turned the boat into a drifting inferno. It was later said that glare from the flames could be seen as far away as Memphis.

Passengers on the overcrowded vessel faced an impossible choice- drown or be burned alive. Many of those who jumped overboard clung to wreckage or semi-submerged trees along the shoreline while others drowned or died of hypothermia. Leaving them behind in the river, the burning Sultana continued to drift until dawn, when she went down near present-day Marion, Arkansas.

Several survivors were rescued when the southbound steamer Bostonia II reached the scene at 3:00 a.m. Others were picked up by different vessels after word of the tragedy spread. Of the estimated 700 who initially survived, 200 later died from burns sustained during the incident.

Approximately 1,800 passengers and crew members were lost. Several bodies were found downriver in the following months, some as far as Vicksburg. Others were never recovered, leaving families with questions that remain unanswered to this day.

What Happened on the Sultana?

An official inquiry concluded that the cause of the Sultana explosion was mismanagement of water levels in the boilers. The twists and turns of the river made the boat list from side to side as she traveled, but the movement would have been more dramatic because she was top-heavy from severe overcrowding.

The four boilers were side-by-side and interconnected, so water would run out of the highest boiler during each turn, creating hot spots. When the Sultana tipped the other way, the influx of water into the empty boiler hit these spots, creating steam and pressure rise. Investigators stated that this outcome, combined with the faulty boiler repair, resulted in disaster.

In 2015, Pat Jennings, Principal Engineer of Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, which was founded in 1866 because of the disaster, identified three factors leading to the explosion:

- The boilers were constructed with a metal called Charcoal Hammered No. 1, which tends to become brittle after prolonged heating and cooling. For this reason, it was no longer used to manufacture boilers after 1879.

- The Mississippi River water used to feed the boilers was dirty. Dirt usually settled on the bottom of the boilers or caused hot spots by creating clogs between the flues.

- The tubular boilers contained 24 tightly-packed horizontal five-inch flues. The density made them difficult to clean, leaving dirty sediment free to form hot pockets. When two more boats with tubular boilers exploded after the Sultana, this boiler design was removed from use.

In his excellent presentation to the National Board of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspectors, Jennings told his audience, “(The boiler was) not even three years old; it has burnt, blistered plates; it has been repaired twice in the past two months; and it had already been retubed. This boiler was in horrible condition and was almost destined to explode.”

He added that Captain James Cass Mason, who had been in command of the Sultana, had been bribed to take on hundreds of freed Union prisoners of war at Vicksburg, overloading the boat.

The conclusion? Human greed and error ended in tragedy, and not for the first time.

Coal Dust and the Sultana

Survivors reported seeing people running across the decks after the explosion, covered in coal dust. Others, like Otto Bardon and Wiley J. Hodges, were hit by flying pieces of burning coal. So did coal dust intensify the outcome?

Mine explosions occur when coal dust comes into contact with a heat source: usually a methane explosion. In the case of the Sultana, the catalyst was the boiler explosion, which would have ignited the stored coal and dust spread across the boat. Although the disaster was not a dust explosion per se, a deadly combination of poor safety standards, improper repairs, and widespread combustible dust produced an incident that killed hundreds of people who managed to survive the horrors of the Civil War.

What are the Lessons Learned?

The Sultana disaster is more than a history lesson. It’s a reminder that complacency can kill; profit over safety is never acceptable. Shoddy repair jobs, cheap parts replacements, and dangerous practices in a combustible dust environment still take lives over 150 years after the Sultana exploded.

We will only see change when we are willing to question and, when necessary, report unsafe practices. As Pat Jennings told the National Board of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspectors, “You have to pay attention, and when you hear something that doesn’t seem right, question it, because the work that you do makes a difference.”