Updated December 2, 2024 Authored by Rose Keefe

Between May 20 and September 13, 1919, four grain elevators in the U.S. were destroyed by grain dust explosions, leaving 70 people dead and 60 injured.

Three of these grain elevator explosion disasters- Milwaukee Works, Port Colborne, and the Douglas Starch Works explosion- have been remembered in regional histories and referenced in dust explosion studies. The fourth, however, has not.

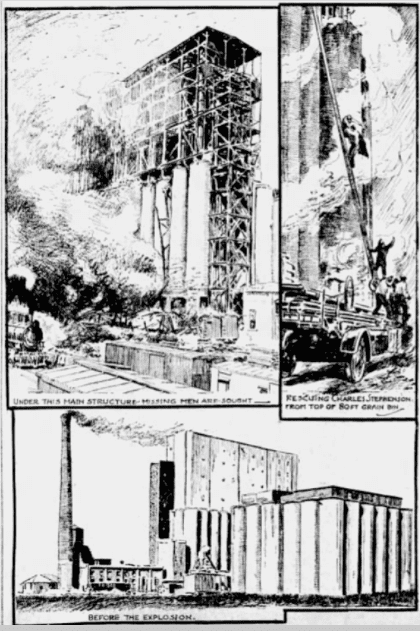

“Under this main structure missing men are sought.”

“Rescuing Charles Stephenson from top of 80ft grain bin.”

“Before the explosion.”

Even its brief Wikipedia mention only refers to it as a “large terminal grain elevator in Kansas City” lists how many were killed or injured, and the grain elevator explosion, “Originated in basement of elevator, during a cleanup period, and travelled up through the elevator shaft.”

There is no company name and no overview of what happened, with the grain elevator explosion.

This lack of grain elevator explosion acknowledgement is surprising. When the Murray Grain Elevator was torn apart by a dust explosion on September 13, 1919, fourteen men were killed and 10 seriously injured. The community lost a key employer during the post-WWI recovery period and families lost husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers.

A dangerous grain facility ignored.

Worst of all, the grain elevator explosion could have been prevented. The grain elevator failed two inspections in the same month and was pronounced ‘dangerous’ both times. Sadly, by the time management paid attention, it was too late.

This article may be the first to tell the story of the Murray Grain Elevator explosion and show what went wrong. As you’ll see, the events leading up to the grain elevator explosion disaster are being replicated even today, and if lessons aren’t learned, more lives and livelihoods will be lost, from grain elevator explosions, and a dust explosion.

September 5, 1919

J.O. Reed was alarmed. As an inspector for the U.S. Grain Corporation, he visited grain elevators across the country and reviewed their operations and safety standards. Reed had seen a lot of facilities that needed work, especially after the war ended, but the Murray Grain Elevator had him worried.

Built in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1905 and located at the north end of the Armour-Swift-Burlington bridge, the grain elevator was owned by the Federal Grain Company. The main building and two storage tanks, which were built from steel, concrete, and tile, contained modern grain processing equipment.

Although its designers and owners touted the grain elevator as fireproof, Reed knew that in its current condition, it was not explosion-resistant.

He made the following observations in his notebook:

- Only the floors were clean. Overhead, suspended grain dust had accumulated on the flanges of the ceiling I-beams: in some places, the grain dust piles were so high that any further build-up tumbled to the floor.

- There was an excessive amount of dust in the shaft containing the stairways, elevator, and main rope drive.

- Grain Dust was piled in the tunnels leading underneath the storage tanks.

- The basement was especially dusty, especially on the trunking of the dust collector. This grain dust was, Reed noted, “very black, old, fine and dry.” There was a huge accumulation of grain dust under one large machine, possibly a conveyor belt: workmen had swept around but not underneath it.

- The grain dust was several inches thick on and underneath two grain cleaning machines located in the northern end of the working floor. The switch and fuse boxes were very dusty.

Equally prominent were potential ignition sources:

- There was a hot bearing on the countershaft driving the fan on the top floor, with a great amount of oil on the journal.

- One of the extension cords on the top floor was in poor condition and worn at the socket. Not too far away was a partially-filled fire extinguisher.

- Carbon filaments were used for lighting everywhere in the plant. There was no protection on electric light bulbs (almost all these bulbs were extremely dusty) and no vapor-proof bulbs were used.

When Reed confronted the superintendent with his findings on the grain elevator explosion, the man said that the plant was only dirty because the fan on the dust collecting system had broken down before the visit. Reed didn’t buy it- he had seen that the fan was in operation. He also knew that this amount of dust took months, not hours, to accumulate, even with dust collection systems.

Exasperated and concerned, he decided to show the workers what could happen if these conditions continued. After ordering a temporary halt to operations, Reed called everyone into the engine room, where he picked up a piece of waste, dipped it in oil, and lit it. After dropping the burning waste on the floor, he shook a dusty sack over it, producing a small explosion and flash fire.

There is no record of how the superintendent or workers responded, but Reed later recalled that he told them to “clean up or shut up.” (One newspaper alleged that he actually said “clean up or blow up.”) At the end of his report, he wrote, “This plant is dangerous and even though fireproof, will explode if its present condition is permitted to exist.”

Another inspection followed on September 12. The report noted that plant maintenance was still poor and recommendations from the September 5 inspection were yet to be implemented.

With no heed given to warnings and inspections, the grain elevator explosion disaster struck.

September 13, 1919

That morning, a flurry of cleaning activity began at the Murray Grain Elevator. The second inspection report had been especially scathing and the dangerous housekeeping issues could no longer be ignored.

The cleaning crew was still at work when, at around 2:10 p.m., a maintenance man named Charlie Tatum noticed blue flames shooting out of electric light wires while he was cleaning grain dust and dirt out of Boot No. 3. Tatum had no time to react before he was caught in what he later called a ‘cyclone’ and loud explosion noise, with a blast wave, that tore off his clothing and covered him in debris.

The grain elevator explosion blew out sections of the main building’s walls and roof and damaged the huge grain tanks on the west side of the property.

The initial explosion caused Timbers and pieces of terra-cotta brick to fall upon the structure containing the elevator’s power sources and injured people inside. The blast wave traveled to nearby homes to shake, breaking windows and cracking plaster walls, causing structural damage.

There were around 40 men in the elevator at the time of the grain elevator explosion. Some were blown clear of the building while others staggered from the ruins with their clothing burned off. One man, George Zarzee, found himself in a wheat field 350 feet away.

J.D. Snowdon, an inspector for the Missouri State Weighing and Inspection Department, was reviewing weighing operations on the 10th floor when the grain elevator explosion happened.

“We were (at) the south end of the building when the initial explosion occurred,” he later told the Kansas City Star. “There seemed to be a great tearing and rending of everything in the building and then we were enveloped by a blue flame. It seemed to stay there for perhaps one and a half minutes and then disappeared.”

He and another man who had been working nearby managed to reach a damaged fire escape and scramble their way to safety.

“There were two men working on the floor above us,” Snowdon said sadly. “I don’t know what happened to them.”

Snowdon and his companion were luckier than others. One young man, Charles Stephenson, was working with two other men on top of an 80-foot-tall grain tank when the explosion burned their clothing and seared their flesh, leaving terrible injuries.

Caught in the explosion, deranged by pain, crying for an end to his misery.

As soon as he could move, Stephenson staggered to the edge of the roof.

“For God’s sake, save me,” he cried to the crowd below. “I’m burned til I can hardly move.”

The onlookers shouted at him to wait, as the fire department was en route. Deranged by pain, Stephenson then extended his bleeding hands and begged the people below to move so that he could jump and end his misery.

His wife pushed her way forward and begged him to think about their four-month-old baby.

“Wait, Charlie, they’re coming,” she yelled. “The baby needs you, wait! They’ll save you, wait!”

Stephenson didn’t acknowledge her. Instead, he put one foot onto the raised edge, but before he could leap, his two co-workers tackled him despite their own injuries. They wrestled him to the ground and held him in place until firefighters extended a ladder and rescued all of them.

Although Mrs. Stephenson saw her husband saved, other women suffered terrible losses that day. The Kansas City Star reported:

“As the torn and bleeding forms of the victims were lifted from the wreckage, the women pushed forward to see if it were John or Will or Rob. A painful cry from an old mother who covered her face with her apron was evidence enough of identification.”

Faith in a “fireproof” elevator meant there were no fire safety resources near at hand.

Firefighting efforts by the fire department were hindered by the fact that the nearest hydrant was 8,000 feet away. It was a shocking oversight that may have been due to the elevator’s so-called ‘fireproof’ construction. The fire department was unable to run a sufficiently long hose connection to the burning buildings until 3:30 p.m., at which point the damage had intensified. Thirty grain-filled box cars standing near the south end of the elevator also caught fire. The fire department and emergency personnel worked with caution, “even in rescuing and treating badly injured survivors.”

Once the flames were under control by the fire department, the intense heat of the debris prevented fire department rescuers from searching for missing men. To accelerate cooling, the fire department and firefighters ran a stream of water through the tunnel that ran under the first floor of the work building.

During the ensuing search for the fire department, the list of dead and severely injured grew, until it finally stopped at 14 deaths and 10 injuries. H.J. Smith, president of the Federal Grain Company, which owned the Murray Grain Elevator, estimated the loss in product and property at $650,000 dollars. It was a disaster of such magnitude that an investigation immediately followed.

Investigating the explosion and its source

Three men were appointed to head the investigation:

- Dr. J.D. Price, engineer in charge of the Bureau of Chemistry in the Department of Agriculture. Dr. Price was also the director of a campaign to eliminate the dust explosions in mills and elevators.

- J.O. Reed, the investigator whose warnings were heeded too late.

- Vernon Fitzsimmons, who headed the government’s ant-dust explosion campaign in the Northwestern District.

After inspecting the damage and interviewing witnesses, they concluded that the grain elevator explosion originated in the basement. The dust explosion propagated up through the manlift tower on the side of the elevator and blew out the walls with unusually aggressive force. Pieces of the 16-inch concrete wall were found dozens and, in some cases, hundreds of feet from the site and the entire working shed was blown away, leaving a demolished grain dryer behind.

“I don’t think there is an explosion which has ever occurred in a grain elevator in this country in which there was more force displayed,” J.O. Reed said.

Coming to terms with the explosion’s aftermath

On September 19, the coroner’s jury ruled that the cause of the explosion was unknown. Charlie Tatum repeated his story of seeing blue flames coming out of electric light wires, but there were also allegations that someone had lit a cigarette in an area not designated for smoking.

No one would be held criminally liable for the disaster, but those who lost loved ones may have taken comfort in the fact that it inspired change. Grain elevators that previously lacked sweepers quickly hired them while those with a cleaning crew engaged additional men in order to keep the plant in as good a condition as possible.

There was also renewed activity among fire departments, fire underwriters, and insurance professionals who had considered fireproofing to be sufficient protection for grain elevators. Now they were re-inspecting facilities for dust explosion hazards, as physical evidence.

One inspector, H. J. Helmkamp, later wrote:

“The terminal elevators in Omaha and Kansas City, with the possible exception of one or two, I found to be the cleanest that I have ever found in any one locality and I think that this is the one big improvement which can be said to result from the Kansas City explosion. Nearly all recommendations were gladly received and in many cases I was asked to pay particular attention to certain parts of the plant or to certain equipment in the plant in order to determine the dust explosion hazard. At all times every possible courtesy was shown to the men engaged in this work.”

Over 100 years have passed since the Murray Grain Elevator exploded.

During this time, thousands more have died in similar incidents, including grain elevator explosions, across the world. Although the mandatory dust hazard analysis imposed by NFPA 652 is a step in the right direction, it doesn’t affect countries that observe different standards, and even those governed by NFPA can -and probably will- resist safety measures that impact profitability. For this reason, these lessons from the past should be treated as warnings that ring true even today. On June 8, 1998, an explosion at the DeBruce Grain elevator, the largest grain elevator in the world at the time, remains one of the most significant industrial disasters in the agricultural sector. This disaster designation released the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to dispatch to this county. Located in Wichita, Kansas, in Sedgwick County, the DeBruce Elevator was, at the time, one of the largest grain storage facilities in the world. The Debruce grain explosion catastrophic event, highlights the critical importance of safety measures in grain handling operations, explosion prevention, and grain dust control systems, to prevent a a dust explosion.

Similar catastrophic dust explosions occurred on December 22, 1977, at the Continental Grain Company’s grain elevator, in the small town of Westwego, Louisiana, and at the Superior Grain Elevator in Superior, Wisconsin, causing severe damage and injuries. The explosion happened in the loading tower of the Viterra Grain Elevator, where workers were performing normal operation tasks such as transferring grain into storage. The incident triggered an active fire, drawing an immediate response from the Superior Fire Department and other first responders. The fire department faced significant challenges in extinguishing the flames and stabilizing the site, but their efforts prevented further escalation. Investigations revealed that combustible dust accumulation was a key factor in why the explosion happened, emphasizing the importance of safety in normal operation.

The aftermath of the Viterra Grain Elevator incident showcased the resilience and skill of the Superior Fire Department. As the fire department battled the active fire in the loading tower, the fire department demonstrated exceptional expertise in managing industrial emergencies. The damage to the Superior Grain Elevator highlighted the critical need for dust control in facilities operating under normal operation conditions. This tragedy, where the explosion happened, serves as a sobering reminder of the risks associated with combustible dust and the vital role played by fire department services. Thanks to the dedicated work of the Superior Fire Department, the situation was brought under control, preventing additional harm to workers and infrastructure.

Over 100 years have passed since the Murray Grain Elevator exploded. By learning, from past incidents and multiple explosions, and recently the Debruce grain elevator explosion, and continuously improving safety practices, fire department training, and preventative maintenance, a safer working environment will be created for everyone in the grain handling industry.

Resources:

- Kansas City Star

- Kansas City Times

- Proceedings of conference of men engaged in grain dust explosion and fire prevention campaign, conducted by United States Grain Corporation in cooperation with Bureau of Chemistry, United States Department of Agriculture. (1920). New York: U.S. Grain Corporation.