Updated August 15, 2024 Authored by Rose Keefe

On May 20, 1919, When 15-year-old Bernard Kilps arrived for his morning shift at the Smith-Parry Grain Elevator in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he probably anticipated another routine workday. Bernard worked on the second floor of the elevator warehouse, preparing grain for shipment, and proudly took his wages home to his parents each week.

And it did start off routinely; the morning began without incident. Then, at 11:15 a.m., while Bernard was hefting bags of grain, an explosion happened, and shook the elevator buildings. He had barely registered the shock when flames erupted all around him.

Disoriented by the explosion and deafened by the roar of the fire, Bernard staggered wildly around, looking for an escape. The exit was blocked off by flames so he stumbled toward a chute that was used to load bagged grain onto freight cars.

He jumped into it and slid down to the ground, where he was quickly surrounded by people who had come running when they heard the explosion. One of them was his 22-year-old brother, Henry, who worked at a nearby plant, when the explosion happened.

Bernard’s family was lucky their son made it out alive. Other families weren’t. Three people died, all men – Joseph Jereczek, 32, Harry Peck, 18, and Isaac Chevalier, 41. Four others were seriously injured and rushed to Hanover Hospital where, later that night, hospital officials confirmed they were in stable condition.

The Smith-Parry Grain Elevator was a relatively new structure built in 1917.

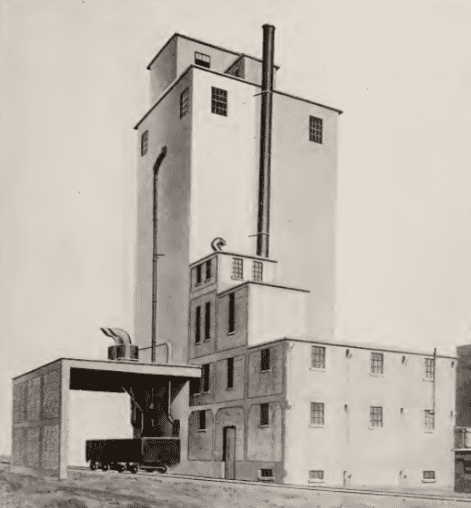

The Smith-Parry Grain Elevator was located between Thirty-Sixth and Lincoln Avenues in Milwaukee. The mill, maintenance facility, and the warehouse, which were constructed from concrete, sat on a large piece of land near railroad tracks. Three side tracks entered the plant to load and unload grain shipments.

The elevator was a relatively new structure, for the manufacturing process, having been built two years prior, in 1917, to produce feed for poultry, horses, and dairy cattle. Later on, it began handling popcorn and built a crib 100 feet long and 20 feet wide to accommodate this new offering.

Investigators concluded that sparks from machinery friction ignited the grain dust.

The explosion destroyed the elevator buildings, resulting in $100,000 worth of property damage from the explosion remains and debris. Investigators concluded the cause of the explosion had occurred when sparks from machinery friction ignited the grain dust scattered throughout the premises, and caused a small fire to start the explosion. No one was ever held responsible for cause of the explosion.

The Smith-Parry Grain Elevator explosion did not get a lot of attention from regulators, the county sheriff’s office, or from the press because of the comparatively low death count. During the early 20th century, workers in the United States faced perilous health and safety risks on the job regularly – although efforts were underway by unions and some government agencies to improve these conditions. Workplace injury and death were quietly accepted as a normal occupational hazard, with some industries being more dangerous than others. The Walworth County Sheriff’s Office was established in 1839 in the Territory of Wisconsin, 9 years before Wisconsin became a state, but had not additional information or records for the explosion. The Sheriff’s Office and Sheriff’s deputies, at the time, may not have been familiar with combustible dust explosions. In addition, the Sheriff’s Office and Sheriff’s deputies had limited resources and funding at the time. With two previous and similar incidents, the Walworth County Sheriff’s Office and Sheriff’s deputies could have learned some safety information. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the Falk’s Bavaria Brewery was Milwaukee’s fourth-largest, trailing only Pabst, Schlitz and Blatz. On July 4, 1889, the brewery complex was nearly leveled by a fire that was, in the Milwaukee Sentinel’s opinion, “the largest, the fiercest and the most destructive that ever visited Milwaukee.” A second fire occurred on Aug. 30, 1892, barely three years after the Fourth of July blaze, and flames destroyed the new Falk corporation brew house, grain elevator, malt house and refrigerator building.

What makes this tragedy and explosion especially significant is that it was the first of four grain dust explosions in 1919. By the time summer was over, 70 people would be dead and 60 more would be injured. The other explosion incidents are covered in the following articles:

- The Day Cedar Rapids Shook- The Douglas Starch Works Plant Explosion of 1919

- Dangerous Dust: The Port Colborne Grain Elevator Explosion of 1919

- Forgotten Disaster- The Murray Grain Elevator Explosion of 1919

Over 100 years later, we continue to fight against the belief that workplace injury or death is a normal occupational hazard.

Feed and grain industry workers continue to die and suffer injury in preventable dust explosions and fires. Although progress has been made through education, advanced engineering controls, and improved grain handling protocols, incidents are still happening more than they should. To curtail the risk, spreading knowledge and awareness of grain dust explosion hazards needs to remain a priority.

You can help! If you have an incident you would like to report anonymously, are looking for somewhere to share your safety communication or observation, or if you’d like to join and contribute to one of our Global Working Groups, visit www.dustsafetyshare.com.

Sources

- Wausau Daily Herald

- Decatur Herald

- Portage Register-Democrat

- 2006 Falk Corporation explosion

- Fires, Floods, and a Resilient Spirit

- The American elevator and grain trade. (1917). Chicago: Mitchell Bros. & Co