When employees at the Dominion Grain Elevator in Port Colborne, Ontario, Canada, arrived for work on August 9, 1919, they may have had an inkling of the danger they were in.

Working in the grain handling industry, combustible dust was a constant threat. Three months earlier, on May 20, a feed mill in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, exploded, killing three people and injuring four others. Two days later, another explosion occurred at the Douglas Starch Works in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. This time the devastation was worse: 44 dead and 30 injured.

These Dominion Grain Elevator workers might have known that in their industry, disaster could strike anytime and anywhere. But with good jobs being scarce and Canada struggling to recover from the First World War, all they could do was hope that it never happened there.

Built for Strength

The Dominion Grain Elevator opened in 1908 and quickly assumed a central role in grain movement through the Great Lakes. It was made from reinforced concrete and equipped with facilities for loading and unloading both railway cars and ships.

By 1913, more storage bins were installed, doubling the elevator’s total capacity to over two million bushels and increasing its importance in the North American grain trade. Six years later, in 1919, the Ottawa Journal would call it “the finest elevator in America.”

The Explosion

Some of the elevator employees spent the morning of August 9 loading wheat onto a barge, the Quebec, while a group of 27 masons carried out minor repairs on the elevator’s concrete storage bins.

There was some excitement at 11:50 a.m. when a fire occurred in No. 10 lofter, which was one of the many internal legs used to transfer the grain from the lower to the upper system of the elevator’s horizontal conveyors. (A ‘leg’ was a vertical conveyor belt made of leather or canvas and equipped with buckets.) However, it was promptly attended to before the elevator closed down for the lunch break.

After lunch, the masons left, as they only worked half a day on Saturdays. When the other workers returned to the plant, they smelled burning rubber and assumed that a belt in the basement had overheated. Shortly after 1:00 p.m., two employees noticed the conveyor in the lofter head area appeared to be jammed, with smoke issuing from its electric motor. One man on the elevator’s top floor saw smoke and fire on one of the belts and ran. He only had time to get to the first floor before the explosion erupted.

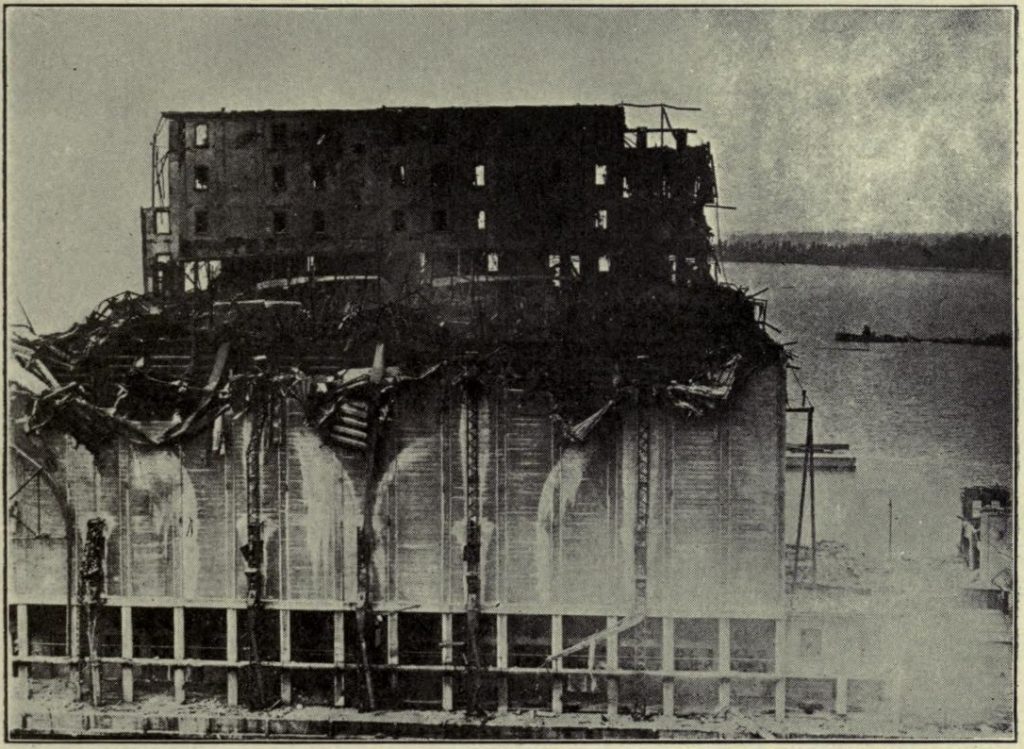

The blast, which occurred at around 1:15 p.m., lifted the grain elevator’s huge concrete roof and blew apart the upper three floors. Flames shot hundreds of feet into the air while charred grain and wreckage were blown a mile and a half around the site, damaging nearby structures. Men were thrown out of the windows into the harbour while a three-foot square hole was blown into Quebec. This damage, combined with the weight of the concrete pieces on the deck, later caused it to sink.

Eight men working inside the elevator were killed. Two men on the Quebec also died when pieces of the elevator rooftop fell on them: the body of mate Joseph Latour was cut completely in half. Sixteen others were left with serious injuries: a flying girder jammed Arthur Montreuil against steaming hot pipes on the barge until a derrick was able to remove it. It took over two weeks to clear away enough rubble from the elevator and the barge to locate all of the bodies.

Once enough debris was removed, the elevator was reconstructed and put back into operation, but the process took over a year and in the meantime, there was a significant disruption in grain shipments to eastern North America and overseas. The financial loss ultimately came to $1,500,000 while the loss of human life was incalculable.

The Investigation

The initial finding determined the heat from the motor of the jammed conveyor had ignited airborne dust, causing it to explode. However, Dr. H.H. Brown, an assistant chemist in the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry, inspected the site soon after the explosion and disagreed.

He relayed his findings to an April 1920 meeting of professionals engaged in grain dust fire and explosion and prevention. His presentation was later included in the published work Proceedings of Conference of Men Engaged in Grain Dust Explosion and Fire Prevention Campaign.

“The first cause that was considered by most men was that a motor had started the explosion due to hot bearings. This was because of the fact that there was dust accumulated on it and there had been a little fire around it before luncheon,” he told the assembly. “But that idea had to be discarded when we considered that the plant was not in operation at the time of the explosion. Inasmuch as the plant had closed down there could have been no dust in suspension at that point.”

When Dr. Brown went down into the elevator’s basement, he found a conveyor belt, running from one of the boots, that had been badly burned. In its immediate vicinity was another conveyor belt that was, in his words, “badly choked, grain thrown all over the floor. It looked… bad, but they thought that that might easily have happened when the belt dropped, as both of these belts had dropped.”

The investigators ascended to the upper floors and found that all of the elevator legs had been damaged, some worse than others. The bin floor was covered over with grain and a number of the walls had been blown out.

Dr. Brown observed that the pile of grain in front of the lofter leg which had opened (and where the buckets were hanging down) was covered with material from above.

“If that belt had burned in two and dropped as a result of the explosion, this material would have been covered with the grain. This indicated definitely that that belt dropped and the grain was on the floor before the explosion.”

He presented two interesting facts for the assembly’s consideration:

- The grain bins had a side-wall construction that allowed for a heavy accumulation of dust. “A distance from the top of the bin to the bin floor of about six feet allowed the explosion to pass through into the other bins, blow through the bin floor and the roof above,” he said. “One reason I believe that the explosion propagated through the bins or got into the bins in the first place, is that there was an opening eight inches wide by the width of the elevator belt, about thirty-two inches.”

- The photos of the damaged building showed that all of the basement windows were drawn in. Broken glass was strewn across the floor, suggesting that the explosion went upwards from the well and throughout the bins.

This outcome was actually an intended result of the elevator’s design – in the event of a fire or explosion, the reinforced walls would direct the force upwards and prevent debris from flying into the surrounding structures and village. While this design helped control damage and injury, concrete chunks and 8” steel beams still flew several hundred feet from the structure, striking the Quebec and killing two men on board.

Investigators also determined that the wheat being loaded onto the Quebec had come from Chicago, where processed grain was known for being dry and dusty. When the dust leads for the elevator’s bins were closed to reduce any product loss, the fans could not clear any airborne particles from the structure, creating prime conditions for a dust explosion to occur.

Regulations vs. Safety

The Port Colborne explosion was one of five major dust explosions that occurred in North America between May 20 and September 13, 1919. In total, over 70 people were killed, several more were injured, and property damage amounted to over $7 million.

These explosions took place in relatively new plants designed to minimize the risk of dust fires and explosions, but the investigators (which included experts from the Canadian and American governments, insurance industry, and grain handling industry) found that design flaws weren’t the issue. The danger existed in current operating policies and regulations.

The Dominion Grain Elevator handled large amounts of dusty grain, but Canadian government regulations prohibited the removal of the dust. If the elevator received 500 tons of grain, the same amount had to be shipped out, even if a significant percentage of that weight was grain dust. Therefore, even brand-new elevators with state-of-the-art ventilation systems could not be used to prevent airborne dust accumulations, as any blow-off could affect the shipment weight.

At the inquest, general manager W.F. Fawcett acknowledged that when it came to dust explosion safety, elevators in North America were between a rock and a hard place. He said that the grain commission prohibited blowing the dust away from the grain and even sent inspectors around to make sure this mandate was being followed.

“We must deliver absolutely the same amount of grain as we take in,” Fawcett explained. “If there is any loss, the elevator must stand it.”

He pointed out that two years previously, the Maple Leaf Milling Company nearly lost its license because it used the dust blowers on incoming grain shipments. When ordered to remove the blowers the company complied but soon restored them. It was only after its license was threatened that the blowers came off for good.

Conclusion

Although over 100 years have passed since the Dominion Grain Elevator explosion, people still go to work at facilities handling combustible dust, never suspecting that it will be their last day alive.

Government policy and regulations have adapted for safer workplace practices. However, in many cases, deadly accidents occur because management is unwilling to bear the financial brunt of newer and safer protection systems. In others, there is a sense of complacency because no catastrophic incidents have ever taken place. Sometimes the problem is a combination of both attitudes.

Whatever the reason, lives continue to be lost in dust fires and explosions, and when cost and convenience stop playing a role in safety system implementation, the trend may finally come to an end.

Thanks to Michelle Mason at the Port Colborne Historical and Marine Museum for use of presentation materials for the 2019 exhibit Deadly Dust: Dominion Grain Elevator Explosion.